Engineering World Health Summer Institute

0 travelers are looking at this program

About Program

The Engineering World Health Summer Institute sends students and young professionals in engineering and science to three countries — Nicaragua, Rwanda, and Tanzania — where their skills are put to use repairing medical equipment that saves patients’ lives. It is the rare opportunity for participants to make an immediate impact.

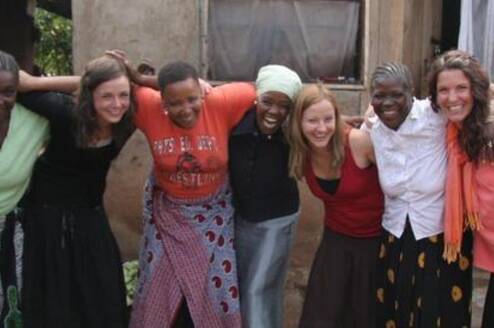

In the Summer Institute, students receive training and hands-on experience working in hospitals and clinics with very few resources. Students are immersed in a different culture, living with local families, working alongside doctors and nurses, and learning a new language. For many, it’s the beginning of a long-term commitment to helping vulnerable patients and communities in the developing world.